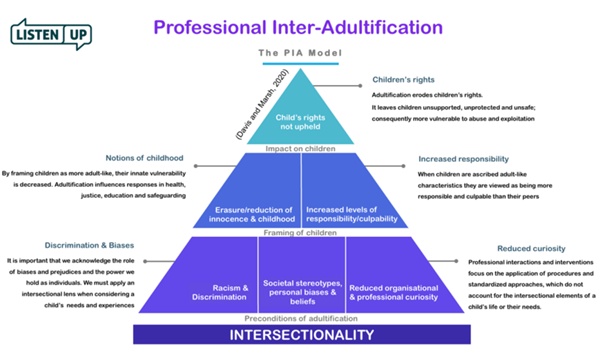

| I’m happy to be writing this newsletter at a point where we are having a bit of a respite from the super-hot weather, thank goodness. Working in this heat has been a challenge, so I hope you have been finding ways to keep cool. I’ve been delivering training to a variety of different audiences, including festival organisers who are preparing staff for events taking place over the summer. No doubt you will have been aware that a report on group-based child sexual exploitation (CSE) was published last week, to incendiary headlines. The well considered report, however, clearly stated there is such limited data on group-based CSE that it is currently impossible to draw robust conclusions about its scale and any statistical relationship of the ethnicity of perpetrators or indeed victims. Though it acknowledged that questions had been raised about these issues and that it was important to supply answers, the data available is currently compromised by the fact that it has not been collected systematically: ‘There is no recent study of the prevalence of child sexual abuse and exploitation in the population. Confusing and inconsistently applied definitions and incomplete data across the police, local authorities, health and the criminal justice system, obscure it. The concept of ‘grooming gangs’, while well-known to the public, is not captured clearly in any official data set.’ [1]Despite this, the report is useful in describing the dynamics of group-based CSE, and the weaknesses in our safeguarding systems that fail to either stop the perpetrators or give sufficient protection, support or justice for victims. One of those weaknesses the report describes in some detail is the phenomenon of ‘adultification’. The report found that girls in care were often not protected because of judgements of adults whose ambivalence towards their welfare meant they could be ‘fast-tracked into ‘growing up’ before their time’. [1]Adultification is when notions of innocence and vulnerability are not afforded to some children who are assumed to be older than their years and not as much in need of protection from abuse compared to other children. This means that they can become much more vulnerable to harm. Research would suggest adultification mainly affects children who are exposed to domestic abuse, experiencing some socio-economic disadvantage, transgender, homeless or unhoused, young carers or (as the CSE report above recognises), children in care. Overwhelmingly though, the group of children who seem most vulnerable to adultification are Black children. Sometimes victims have several of these characteristics that increases their vulnerability to adultification – which means a robust understanding of adultification necessitates an understanding of intersectionality – a theory that acknowledges and examines cumulative forms of discrimination. Another important safeguarding report was published this month by an organisation called ‘Listen Up’. Its focus was an analysis of the systemic adultification in our safeguarding services and how we can best tackle this. Listen Up is a Black-led national research and training organisation, established to amplify the experiences of Black and racialised children in safeguarding research, policy and practice. Again, it’s a great report that is both eye-opening and useful, as it makes several recommendations for improved practice.The case involving adultification that first brought this issue to my attention was the case of ‘Child Q’. I have spoken about Child Q on my training and there is a fair knowledge of what happened in my participants, but I thought it was worth revisiting in my newsletter because the learning it demands from us all is so compelling. |

In 2020, Child Q, a 15-year-old Black female child attending her secondary school, was suspected by her teachers of carrying drugs. Child Q denied this. A search of her bag, blazer, scarf, and shoes revealed nothing of significance. After the school called 101, the police sent out four officers to the school. Child Q was escorted to the school medical room and subsequently strip searched by two female officers, a process that involved her having to remove her sanitary towel as she was menstruating. She was required to bend forward to allow inspection of her bare genitals and anus. No Appropriate Adult was in attendance; teachers remained outside the room and Child Q’s mother was not contacted in advance. No drugs were found. After this, Child Q was directed to carry out a mock exam scheduled for that day as if nothing had happened. Child Q has continued to experience long term mental health problems relating directly to this event. A local child safeguarding practice review, initiated by the local safeguarding partnership in Hackney, was carried out. The overwhelming opinion of this was that Child Q had been exposed to a traumatic incident and had undoubtedly suffered harm. As the review states: ‘Given the context of where and how the search took place, it was impossible not to view these circumstances as anything other than the most serious and significant.’ [4]The review judged that the school had deferred their professional judgement to the authority of the police. They should have been more challenging, seeking clarity about the actions the police were planning to take and questioning their appropriateness. All practitioners were reminded of the need to be mindful of their duties to uphold the best interests of children and hold safeguarding of their welfare as their paramount concern. The review was clear that, having considered the context of the incident, the views of those engaged in the review and the impact felt by Child Q and her family, racism (whether deliberate or not) was likely to have been an influencing factor in the decision to undertake a strip search. In a statement Child Q said: “Someone walked into the school, where I was supposed to feel safe, took me away from the people who were supposed to protect me and stripped me naked, while on my period. I can’t go a single day without wanting to scream, shout, cry or just give up. I don’t know if I’m going to feel normal again. But I do know this can’t happen to anyone, ever again.” [4][Update: at the time of writing, it was announced that the two officers involved in the strip search had been sacked after a police misconduct hearing. Claims of racism and adultification were not substantiated at the hearing.]In the context of what happened to Child Q, the Listen Up report makes for compelling reading. It concludes that, whilst professionals are increasingly recognising adultification as an important safeguarding issue, knowledge of it can be superficial. There is (as in the case of CSE) poor collection of data relating to adultification that can highlight incidence and patterns. It is not yet mentioned in statutory safeguarding guidance. Professionals could sometimes approach the subject with a degree of defensiveness, as if they were personally being accused of racism. This can impede their ability to cultivate their own professional curiosity and fully reflect on their practice and put the safeguarding of children at the centre of their work. Practitioner development was also hampered by the lack of strategic leadership pushing practical actions. Many professionals expressed lack of trust in the police and their tendency to adultify of Black children. This was echoed by the Black children who took part in the research, who described their experience of adultification at first hand:‘…they are often treated as problems, and as a risk, and that they feel there is an assumption that they are dangerous and criminal before they are seen as children. Consequently, adultification impacts on their safety, confidence, trust, and aspirations. ’Perhaps the most moving part of the report is simply its implicit plea to treat all children with love and care, something that adultification denies them. It quotes evidence taken from practitioners who: ‘spoke about ‘the absence or removal of love and care’ in safeguarding practice as contributing to the adultification of children. The perception that some children are not treated as if they are deserving of, or needing, love and care, led them to challenge the sector to think about ‘how we are loving and caring for’ the children who encounter it. This echoes similar findings from research conducted in North America which shows that Black girls as young as five years old are perceived as not needing nurture or care. A safeguarding system which enables adultification is not only failing in its duty to safeguard children but is harmful to them.’ [3]  Further reading1. To read the full report on National Audit on Group-Based Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse June 2025 by Baroness Casey: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/685559d05225e4ed0bf3ce54/National_Audit_on_Group-based_Child_Sexual_Exploitation_and_Abuse.pdf 2. For a clear and easy to read guide to the audit and its main conclusions, this is an excellent summary carried out by the NSPCC: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/2025/summary-national-audit-group-based-child-sexual-exploitation-abuse?utm_campaign=20250623_KIS_CASPAR_June23&utm_content=Summary%20of%20the%20National%20audit%20on%20group-based%20child%20sexual%20exploitation%20and%20abuse&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Adestra 3. Pushing Forward Testing learning on Adultification in Child Safeguarding Practices in England, Listen Up, Esmee Fairburn Foundation June 2025: https://listenupresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Pushing-Forward_Report.pdf 4.Local Child Safeguarding Practice Review Child Q, Gamble March 2022: https://chscp.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Child-Q-PUBLISHED-14-March-22.pdf For more information on all the courses and services I can offer, please visit my website www.mandyparrytraining.co.uk – or contact me directly at mandyparrytraining@gmail.com |